Introductions to Psychometric Techniques: Differential Item Functioning, Part II: Illustrative Analysis

By: Lucas J. Friesen, Associate Psychometrician at Paragon Testing Enterprises; Bruno D. Zumbo, Paragon UBC Professor of Psychometrics & Measurement

This is the second of a two-part series discussing differential item functioning. Part I provided an overview of DIF as a concept, and a background for discussing some of the methods used to examine DIF. Part II will provide an illustrative example of DIF analysis as it is conducted at Paragon Testing as a part of our ongoing commitment to quality and equitability in testing. The analysis in question was part of an exploratory pilot analysis intended to determine the best methods for detecting DIF in Paragon’s tests.

This analysis used logistic regression (LogR) to assess DIF on the Listening and Reading components of the CELPIP tests. The groups being compared were males and females, as reported by test-takers when they register to take a CELPIP test. Test takers who did not provide gender information were excluded from analysis. The scope of the analysis was all of the items in use during 2017, which includes both items introduced via field testing and items used as anchors in performing IRT equating for the Listening and Reading components. Items which had below 200 responses from either group during 2017 were excluded from analysis, as too few responses from either group decreases the accuracy and interpretability of LogR results. Finally, test takers from the two groups were matched on their IRT ability parameter (θ), rather than total test scores. This was done because it allows for comparisons between test takers who received the same items, but not the same test form, as is often the case.

In other words, for each item which received greater than 200 responses by both males and females in 2017, the LogR technique creates a probability model wherein the probability of correct response to an item is the dependent variable, gender differences (coded 0, 1) and θ are independent variables used to detect the main effect of group differences (uniform DIF), and the interaction between gender and theta is used to detect non-uniform DIF. The main effect of gender is uniform DIF, and the interaction effect of gender is non-uniform DIF.

Finally, the difference in the -2 log likelihoods of the models is compared to a chi-squared distribution with two degrees of freedom. If the difference is statistically significant at α = 0.05, the item is flagged as exhibiting DIF and the effect size is examined to determine the degree of DIF (See Shimizu & Zumbo, 2005 for further explication of the LogR technique for detecting DIF in language assessment).

The analysis was performed using software developed for R by Magis et al. (2010) which facilitates the speed and reporting of DIF analyses for a variety of detection techniques, including LogR. Items were classified as exhibiting DIF according to the effect size criteria of Jodoin and Gierl (2001). In these criteria, items are classified as exhibiting one of three levels of DIF: “A” – Negligible (change in Nagelkerke R-squared < 0.035), “B” – Moderate (change in Nagelkerke R-squared between 0.035 and 0.070), or “C” – Large (change in Nagelkerke R-squared > 0.070).

Results

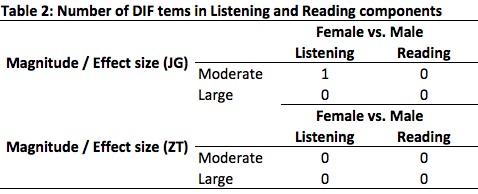

The present study revealed that in 2017, of the items examined for DIF, one item exhibited B-Level DIF according to the Jodoin and Gierl (JG) scale, and none exhibited DIF according to the Zumbo and Thomas (ZT) scale. For reference, in the ZT scale “A” means negligible bias (change in Nagelkerke R-squared < 0.13), “B” means moderate bias (change in Nagelkerke R-squared between 0.13 and 0.26), and “C” means large bias (change in Nagelkerke R-squared > 0.26). The results are summarized in Table 2, below.

Table 2:

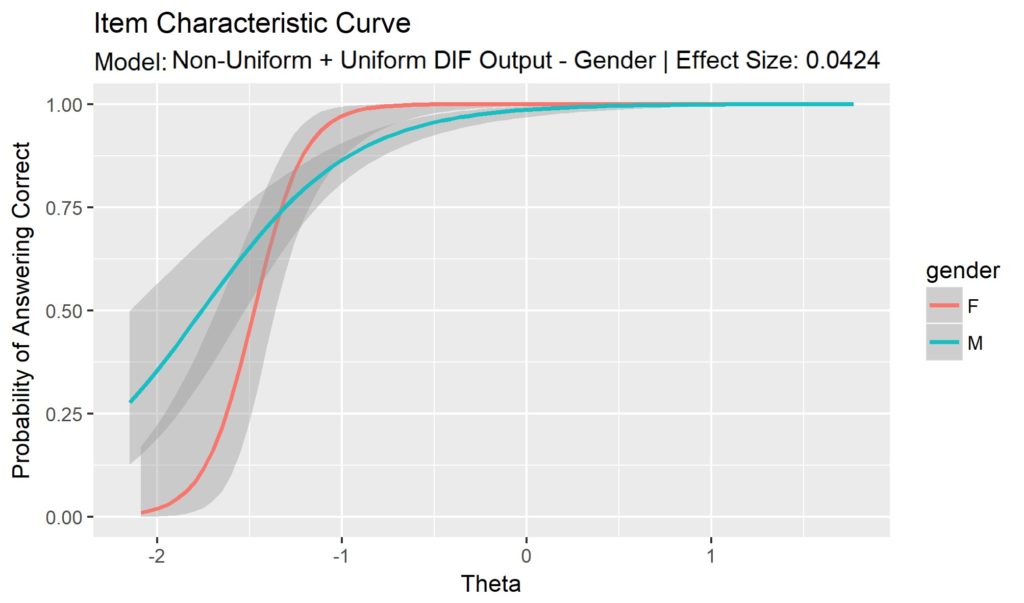

The following plot shows the item characteristic curve of the item which exhibited B-level DIF. An investigation into this item shows some indication of why it may be exhibiting gender DIF. Firstly, there is a much wider standard error (represented by the faded grey bands) at the low end of theta distributions than the high end. This is because there are relatively fewer responses in the low-theta range than for both males and females. In addition, the sharp drop in expected probability of answering the item correctly at approximately θ = -1 indicates that this item was almost never answered incorrectly, except by test takers at the lowest theta-levels. This sharp difference in proportions of responses is a potential source of estimation bias in logistic regression parameters (King & Zeng, 2001).

Discussion

Given the high-stakes usage of the CELPIP-G and CELPIP-G LS in Canadian citizenship and immigration decisions, it is important to confirm that there is no advantage or disadvantage to belonging to a certain social group, especially one which is protected from discrimination by Canadian law, as is the case with gender. Thus, the purpose of this study was to assess DIF on the CELPIP Listening and Reading components between male and female test takers. The analysis presented above assessed Listening and Reading items on the CELPIP tests for DIF between males and females using binary logistic regression. The results showed that there is no indication of beyond-negligible DIF on any items assessed using either the Zumbo-Thomas scale, while one item did exhibit B-level DIF on the Jodoin and Gierl scale. However, closer inspection of the item revealed that that gender DIF is likely an artifact of a skewed population of responses for this item. Because it has so few incorrect responses, a small variation in the number of incorrect responses between males and females is magnified and reflected as DIF. In order to combat this effect, future studies will be run with restrictions on the minimum number of correct and incorrect responses from both groups (Male/Female), in addition to the minimum population sizes for both groups on each item.

Overall, this analysis has indicated that the item development processes and procedures currently in place for quality control in Listening and Reading item development are performing well with respect to DIF between males and females. This means that scores on the Listening and Reading components of the CELPIP tests may be understood as estimates of English language proficiency which are unbiased with respect to gender. While further research is necessary to assess DIF on the Reading and Listening components of the CELPIP tests, the results of the present study are seen as being a positive indicator that the CELPIP-G and CELPIP-G LS tests are performing as intended, and not (dis)favouring test takers on the basis of gender.

References (Combined between Parts I and II)

Aryadoust, V., Goh, C. C. M., & Kim, L. O. (2011). An Investigation of Differential Item Functioning in the MELAB Listening Test. Language Assessment Quarterly, 8(4), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2011.628632

Ferne, T., & Rupp, A. A. (2007). A Synthesis of 15 Years of Research on DIF in Language Testing: Methodological Advances, Challenges, and Recommendations. Language Assessment Quarterly, 4(2), 113–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434300701375923

King, G., & Zeng, L. (2001). Logistic Regression in Rare Events Data. Political Analysis, 9(2), 137–163.

Jodoin, M. G., & Gierl, M. J. (2001). Evaluating Type I Error and Power Rates Using an Effect Size Measure With the Logistic Regression Procedure for DIF Detection. Applied Measurement in Education, 14(4), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1404_2

Lee, Y.-H., & Zhang, J. (2010). Differential Item Functioning: Its Consequences. ETS Research Report Series, 2010(1), i–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2010.tb02208.x

Magis, D., Béland, S., Tuerlinckx, F., & De Boeck, P. (2010). A general framework and an R package for the detection of dichotomous differential item functioning. Behavior Research Methods, 42(3), 847–862. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3.847

Miller, R. G. J. (1981). Simultaneous Statistical Inference (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. Retrieved from //www.springer.com/gp/book/9781461381242

Moses, T., Miao, J., & Dorans, N. J. (2010). A Comparison of Strategies for Estimating Conditional DIF. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 35(6), 726–743. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998610379135

Penfield, R. D. (2001). Assessing Differential Item Functioning Among Multiple Groups: A Comparison of Three Mantel-Haenszel Procedures. Applied Measurement in Education, 14(3), 235–259. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1403_3

Raju, N. S. (1988). The area between two item characteristic curves. Psychometrika, 53(4), 495–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294403

Ryan, K. E., & Bachman, L. F. (1992). Differential item functioning on two tests of EFL proficiency. Language Testing, 9(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/026553229200900103

Shimizu, Y., & Zumbo, B. D. (2005). A Logistic Regression for Differential Item Functioning Primer. JLTA Journal, 7, 110–124. https://doi.org/10.20622/jltaj.7.0_110

Young, J. W., Morgan, R., Rybinski, P., Steinberg, J., & Wang, Y. (2013). Assessing the Test Information Function and Differential Item Functioning for the TOEFL Junior Standard Test. ETS Research Report Series, 2013(1), i–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2013.tb02324.x

Zumbo, B. D., Thomas, D. R. (1997). A measure of effect size for a model-based approach for studying DIF. Prince George, Canada: University of Northern British Columbia, Edgeworth Laboratory for Quantitative Behavioural Science.

Zumbo, B. D. (1999). A Handbook on the Theory and Methods of Differential Item Functioning (DIF), 57.

Zumbo, B. D. (2003). Does item-level DIF manifest itself in scale-level analyses? Implications for translating language tests. Language Testing, 20(2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532203lt248oa

Zumbo, B. D., Liu, Y., Wu, A. D., Shear, B. R., Olvera Astivia, O. L., & Ark, T. K. (2015). A Methodology for Zumbo’s Third Generation DIF Analyses and the Ecology of Item Responding. Language Assessment Quarterly, 12(1), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2014.972559